A rich performance with the pathos and drama of a new age of technology set within the hardships of war.

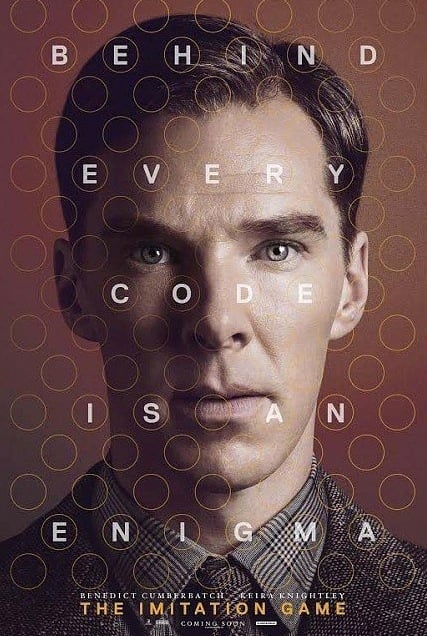

Benedict Cumberbatch pounds out a fantastic performance as one of the greatest nerds of all time, Alan Turing, the inventor of one of the first digital computers. Although the computer itself, built in the legendary Bletchley Park encryption think tank, threatens to steal the show, Cumberbatch (Guillam in “Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy”) does Asberger’s like he wrote the book. He is the ultimate social nebbish while making it perfectly clear that he is also the genius’ genius.

Benedict Cumberbatch pounds out a fantastic performance as one of the greatest nerds of all time, Alan Turing, the inventor of one of the first digital computers. Although the computer itself, built in the legendary Bletchley Park encryption think tank, threatens to steal the show, Cumberbatch (Guillam in “Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy”) does Asberger’s like he wrote the book. He is the ultimate social nebbish while making it perfectly clear that he is also the genius’ genius.

Reuniting with Cumberbatch from “Tinker, Tailor,” Mark Strong reprises his role as super spook in the person of spy-chief Stewart Menzies. Menzies is the dark force behind the ultra-high priority, ultra-top secret program to break the German code Enigma. Turing thinks he is the chess master but it is Menzies who controls the board itself.

The story alternates between Turing’s prep-school childhood, his Enigma days and his post-war lab. A prodigious but socially crippled youth in a rigorous, private boy’s school, he was bullied and had only one friend, with whom he would exchange coded messages. The theme of homosexually lingers in the background for most of the film and pokes out here and there, as in the playful coded message to his chum, “I Love You.” The friend died of tuberculosis before Turing could deliver it.

Keeping the gay issues in the background makes this a better film. This is not because Turing’s horrific treatment at the hands of the nation he saved from the Nazis does not merit airing. In 2009, Prime Minister Gordon Brown officially apologized for “the appalling way he was treated” and the Queen granted pardoned him in 2013 for his 1952 homosexuality conviction. Rather, it is because the development of the incredibly complex, semi-automated code breaking “bombe” by a group of mathematical wizards, chess champions and crossword puzzle demons is one of the great war stories of all time.

Although the Enigma machine had been around for some time, the Nazis had improved it to its WWII configuration of 159 million, million, million possible character combinations, which they changed daily. Some crossword puzzle. Although earlier code-breaking machines had been built, Turing’s was the latest and the greatest.

Cumberbatch’s performance is enriched from darkly humorous to occasionally hilarious by the character of Commander Denniston (perfectly played by Charles Dance—“Gosford Park”). Denniston is a WWI veteran, the perfect model of the British general disciplined to the toenails, but completely helpless within the hurricane of technology that eventually won the war for the Allies. His exchanges with Turing are believable and impossible at the same time. In the end, Turing is the general that breaks the code, but Denniston represents the society that breaks Turing.

Keira Knightley plays Joan Clarke, a beautiful mathematical whiz kid who falls in love with Turing, the wrong man at the wrong time, and whose part in the actual team of code breakers appears to be entirely made up. Although there were a dozen key members of the actual team, none were women. This makes the inclusion of the character in the screenplay all the more mysterious, a poor effort to introduce romantic themes in a story rich with other options. She has worked far better performances in other films.

Even so, her part adds depth to the exquisite sets, costumes, vehicles and sights and sounds of WWII London. The London Symphony’s luscious soundtrack and the overall feel of the film in war ravaged England is as good as it gets. Perfectly drawn characters come in and out of the movie from start to finish. Artfully placed archival footage anchors the fantasy of world class game playing in the mud and death of mechanized warfare.

Finally, when it comes to mise-en-scène, there is the computer itself. Fairly close to the real McCoy, Turing’s creation is an ugly duckling of bolted iron and wooden handles strung with lamp cord wrapped in what appears to be worn-out underwear. The switches, plugs and marvelous syncopated motorized revolving dials are nothing less than the Frankenstein of the computer age. A star is born.

As the persecution against gays, and, indeed, against anybody who has the nerve to see the future, looms ever present, Turing marches on to eventual success and self-destruction. The film begins with a scene from his 1951 Manchester lab, where he is scraping cyanide off the floor. He was using the cyanide for gold electroplating for his latest machine. He died of cyanide poisoning a few years later.