If not for the quick thinking of the Honduran wife of an associate friend of explorer Steve Elkins, this film, Lost City of the Monkey God—which grips you like a real-life Indiana Jones—likely would not have happened.

Elkins spent most of his life wondering about the legends of the Lost City in Honduras and worked for years trying hard to validate his suspicions. However, it was her startling move by grabbing the arm and pitching her husband’s work with Elkins for the Lost City to a passing-by President Porfirio Lobo Sosa that set Elkins’ wheels in motion for the discovery of a lifetime.

Science Channel has a stunning film airing this Sunday that is exceptional. The Lost City of the Monkey God is a gripping account of Elkins’ life work realized. Viewers ride along on the journey to find a settlement whose existence explorers and scholars had long debated.

The documentary posits the question, have we seen everything on the surface of the Earth? We photographed everything, and we’ve plastered our photos on social media, as it seems as if there’s no place left on Earth whose mystery is intact. There are places on Earth that are unknown to us and even hostile to us. This story and the actual event is the dream realized from the hard work of explorer Steve Elkins.

Elkins and a team of archaeologists, anthropologists, scientists, and filmmakers embarked upon a true-life adventure where torrential rains, poisonous reptiles, and deadly disease-carrying flies were endured to search one of the last unexplored places on Earth, known as “Ciudad Blanca” or The Lost City of the Monkey God.

For centuries, adventurers and treasure hunters have searched for the rumored Honduran city built of a beautiful white marble-like stone. Stories are legendary of this purported treasure trove constructed deep within the lush rainforest with impenetrable high mountains, deep rivers, and obstacles guarding it.

The search for it took many lives along the way, as it earned a reputation with locals that even the act of trying to find it was a cursed venture.

Elkins employed LIDAR, the latest cutting-edge technology, to peel away the dense vegetation and map the terrain to locate the city. In his bid to find it, Elkins must build trust with locals, government officials, drug cartels, and the military to make inroads in this compelling adventure.

But can Elkins and his team locate this place filled with invaluable ruins and artifacts to properly excavate and preserve the area from the ravages of time? This excitement is a build that culminated in the excellent news of the discovery and a government and academic body of experts working in sync to preserve an ancient culture.

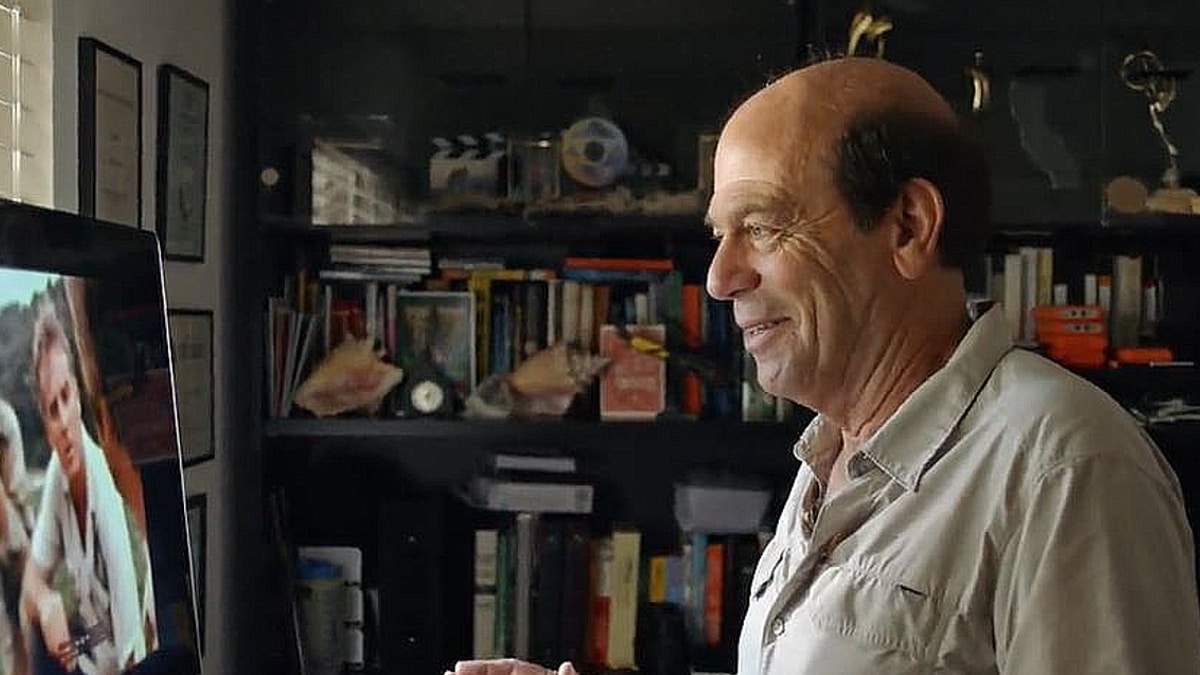

Exclusive interview with Steve Elkins

Monsters & Critics: Your documentary is like an actual Raiders of the Lost Ark, and it’s gripping and exhilarating. Tell me the timeline for you with this lost city subject.

Steve Elkins: It’s not quite the span of my lifetime, but a significant portion of it. It started in 1994, and it’s still going on. So you can calculate how many years that is quite a few, I think, close to 30 years.

M&C: How did you and Douglas Preston, the journalist who became a chronicler of all of these forays into the site connect?

Steve Elkins: After my first venture in 1994, I went to Santa Fe, and I used an engineer from JPL (Jet Propulsion Lab) afterward to do some satellite imaging of the area that I suspected the Lost City might be in.

And at the same time, Doug was interviewing the same engineer for another project, and he asked if there was anything else he was working on and said, ‘Oh, I’m working with this guy about looking for some Lost City somewhere.’ And Doug, being who he is, kept querying him.

And he said, ‘Well, I really can’t say anything because I signed something.’ So the engineer called me and told me about it, and I was interested. So I called Doug, and we had a nice conversation, and it turned out that I was going to Santa Fe, where Douglas lives a short time later, to interview an exploration geologist who claimed he found the Lost City back in 1959, he did find one but in a different place.

I told him what had happened. And he said, ‘Oh, do you mind if I use what happened to you on your first expedition as a framework for some mystery novel?’

I said, ‘Fine, go ahead.’ So a few years later, he wrote a book called The Codex, which I read and was rolling on the floor because he did what I told him, but he fictionalized it and added a lot of murder, mystery, and things like that. But we became good friends after that, and he was interested, and I kept bugging him to join me.

M&C: You have a lot of valuable friendships. Bruce Heinicke and his wife Mabel especially. If not for her grabbing the Honduran President’s arm and pleading the case, you really wouldn’t have found the city.

Steve Elkins: No. Actually, at that time, I would not have had the opportunity to see the whole thing with LIDAR. I mean, I hadn’t spoken to Bruce in 10 years, and I wasn’t sure that I wanted to.

Then he called me on a Sunday morning and said, ‘Steve, how you doing? It’s been ten years. My wife Mabel is in Honduras, and she’s met the President. And he permitted us to look for the Lost City again, [are] you interested?’ I was flabbergasted. And I said yes. Why not? Figuring nothing would come of it, but it actually worked out quite well.

M&C: Tell me about the work of Tom Weinberg and Michael Santori with the LIDAR, their ability to get that raw data so that you could analyze the area as it kicked started the push to go official with the Honduras government?

Steve Elkins: Tom Weinberg has been an old friend of mine from Chicago for many years. And he has been a supporter and has helped me in the early explorations. So I made sure that he was able to participate in this latest venture with LIDAR. He’s always been a good friend and always gave me sage advice and raised money for us back in the nineties.

When we first started, Michael Santori was part of the LIDAR group, the national center for airborne laser mapping of which there are several people. Dr. Juan Carlos Fernandez Diaz was the head LIDAR engineer who actually did the survey, where Michael processed the data that Juan Carlos would collect.

So he, along with some of the people back in Houston, as they were processing the data simultaneously in Houston and Honduras, we collected during the day, processed it overnight. And then one day at breakfast, voila, there it [Lost City] was.

M&C: That has to be exhilarating when you saw that, the first time your eyes saw this information?

Steve Elkins: When I give lectures, there’s a picture someone took of me jumping up and down, which kind of exemplified the feeling because I felt okay, no, one’s going to kill me now for spending all this money.

And they’re not going to consider me a fool. And I’m vindicated after 20 years of research and work.

M&C: What I also found interesting was the pushback from academia, denigrating you as a treasure hunter. They shouted you down, trying to discredit you because you weren’t of their circle, and then the full circle, you were invited to speak at the Explorers Club.

Steve Elkins: Well, I had eleven PhDs on my team in various disciplines, including archeology and anthropology, some major people who made a pretty good name for themselves. So they actually helped me push back against academia because they wrote rebukes to what some of these other people were saying.

It’s a long story. It’s not really for me to go into it now, but I felt it was best to be quiet until the dust settled and let the academics argue amongst each other. And let’s see what happens.

So what we found turned out to be a big deal and it was all corrected, was scientifically correct, and still going on. And it has made an impact. And that’s the way it is. In fact, I think some of our archeologists went to a meeting for the American archeology society, and our critics were supposed to show up, but they didn’t show up.

M&C: It must have been a wonderful feeling when you were invited to talk at the Explorers Club, validation of all of that hard work and the intuition that you had. You had to feel good about that.

Steve Elkins: It felt great. It was a great feeling of vindication. And I got to tell you, when we first the images on LIDAR, we went on the ground, and we actually were touching this stuff and seeing it firsthand. And then, speaking at the Explorers Club, I felt I could have dropped dead and had a good life. Put it that way.

M&C: You wanted to take a few pieces back to show the Honduran government. Hey, this is legit. We need protection. We need to secure the perimeter and get in there and start digging. And we need to expand this. And you had pushback from a few of the academic people on your team saying it had to stay. And that was aggravating. Talk about that moment.

Steve Elkins: Well, it was aggravating, but I had started that conversation on purpose because I wanted it to be out in the open. I wanted people to understand the moral situations, and I think that it is why that the archeologist who stood their ground did so.

They did the right thing, to what their beliefs are in the system. And in the end, it worked because the government supported the project, and they protected it right away.

So, it worked out in the end, but there could have been a situation where we had these soldiers, we had other people there, and the location was no longer a secret.

Once we left, somebody could have gone in there. Some narco leader with money could have ransacked the site. So I mean, that’s the risk. So I may not have always personally agreed with it, but I understood the reason why.

And then the end, because it didn’t get looted, the scientists can better understand by leaving everything in situ. And I purposely wanted them to explain that so we could understand both sides of the argument.

M&C: Let’s talk about the TAFFS security men, Andrew ‘Woody’ Wood. They were invaluable to all of you because they knew what dangers, even before you set foot in the jungle, what you were going to be up against, and sure enough, Fer De Lance drama!

Steve Elkins: Right. Exactly. The hiring of those three guys—which is a book in itself, and how that came about—was terrific. My partner in the project who financed it insisted we get somebody like that to work with us.

And I’m glad we did because these three fellows are jungle warfare experts. So they knew how to survive in the jungle, much better than any of us did. So it was brilliant to have them. They made it very smooth and very safe for all.

M&C: The dangers followed some of you home. Doug Preston suffers from Leishmaniasis still.

Steve Elkins: There are many varieties of it. And it turns out about 60% of everybody on our team, which is quite a few people, all became infected.

The bite of a sandfly transmits it. It’s a little protozoan. It goes in your blood, just like malaria or something. And some people are susceptible in some art and science doesn’t know why some people become symptomatic and others didn’t.

I did not. I had a million bites like everybody else. Those that were symptomatic were treated by the NIH, the National Institute of health, Dr. Fauci’s group back in 2015. And unfortunately, once you get it, you have it for life. Like herpes, it may go into remission, but it pops up again. Doug still suffers from it. And some of the others.

M&C: Will you find yourself going back, and what is the city officially called? Is it the city of the Jaguars or Lost Monkey?

Steve Elkins: Well, certainly in the popular press is Lost City of the Monkey God. It has more names. It’s crazy. According to the legend, it was also called Cuidad Blanca because the stones were allegedly white.

But because we saw a Jaguar sculpture and there were a lot of live Jaguars there, we decided to rename it the City of the Jaguar. So all those names are used intermittently.

And now, the government of Honduras decided to use the indigenous name, Kaha Kamasa, in the local Miskito language.

M&C: How long do you think it’s going to take to excavate this entire area?

Steve Elkins: I’m not sure it’ll be ever activated and entirety because you wind up destroying the jungle, but there is a depth of excavations going in and out, or the two teams that are out there as we speak, I believe, are coming back this week.

It’ll take a very long time, because of the difficult working conditions. And you want to be sure not to destroy the very environment that you’re trying to protect.

Because not only are we trying to learn about the cultural aspects, it’s very precious rainforests that we commissioned a study for, and extinct forms of life and new life forms that no one knew anything about until now. I have to be careful. There’s a balance in how to do this.

Hopefully, those studying all of this will get answers while I’m still around.

Lost City of The Monkey God premieres Sunday, October 31 at 8 PM ET/PT on Science Channel.

Follow the conversation on social media with #LostCityOfTheMonkeyGod, and follow Science Channel on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram for more updates.