Australian mystery thriller with all the grit in the outback and a little more.

David Michôd ups the ante and hauls in a big one in this Aussie thriller set in the desolate outback ten year after the collapse. The collapse? The comedians in the audience will point out that the outback ten years after the collapse looks about the same as it did ten years before the collapse, whenever that was. But that is not the point. The point is that things are bad there. They are so bad that gasoline costs $10 a gallon and people eat dogs. They are so bad that people drive beat up old cars that no one in the present time would touch. They are so bad, yes, believe it, they are so bad that shopkeepers will only accept US dollars.

David Michôd ups the ante and hauls in a big one in this Aussie thriller set in the desolate outback ten year after the collapse. The collapse? The comedians in the audience will point out that the outback ten years after the collapse looks about the same as it did ten years before the collapse, whenever that was. But that is not the point. The point is that things are bad there. They are so bad that gasoline costs $10 a gallon and people eat dogs. They are so bad that people drive beat up old cars that no one in the present time would touch. They are so bad, yes, believe it, they are so bad that shopkeepers will only accept US dollars.

You better believe David Michôd and his co-writer Joel Edgerton know bad. Michod wrote the current king of the Australian crime-thriller genre, “Animal Kingdom,” all by himself. The film featured Guy Pearce and Joel Edgerton in similar roles, although Pierce was a law enforcement office in that film. Of course, in the dystopian future, law enforcement has no meaning whatsoever and the cops and the killers meld into a single, heartless monster capable of doing anything it takes to survive.

Guy Pierce also starred in the legendary down under Western “The Proposition” as Charlie Burns, black-mailed into tracking down and killing his older brother in a no-man’s land of the outback that not even wild men would enter. The dystopian future of “Rover” is much the same as that hideous hiding place. In fact, one of the most fascinating parts of this brooding story is that it could just as well been set in the current time. Everything in the screenplay could have been placed in the present day. Granted, it would not have reflected well on Australia, and perhaps that’s why the dystopian trope was thrown in. Another option would have been to set the story in Texas, in the USA, in a world where they only accept Australian dollars. But, that might have resulted in violence. Texas might have seceded from the union and declared war.

To its credit, the tone of the film comes very close to matching “No Country for Old Men,” word for word, long take for long take, senseless death for senseless death and desolate wasted desert blood bath for desolate blood bath. Michod and Edgerton certainly have the gory close range gunshot effects down. Rated “R” for language and bloody violence, it is hard to imagine a more realistic series of flesh splattering, blood soaked sequences. Unlike the more spectacular martial arts gangster flicks, where a thousand shots are fired for every one that hits anything, when these guys shoot, they hit, up close and personal. Of course, with gas at $10 a gallon, one can only imagine how much bullets cost.

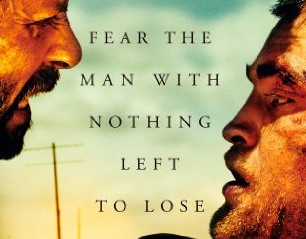

The other lurking specter is the ghost of the Clint Eastwood spaghetti western. The lead character, Eric (Guy Pearce) is a man of few words. He has lost his soul in the trauma of previous sins and this road trip is his last chance at even the smallest measure of redemption. He is damned and he knows it. Having come that far, there is nothing left to lose and not even the heart and mind of the fragile Rey (Robert Pattinson) will stop his rampage.

If Guy Pierce is as good as ever, it is the startling performance by Pattinson that nearly steals the show. Having a track record consisting mostly of profitable but lethally teen-age “Twilight Saga” credits, Pattinson had to buck a huge gravitational pull towards the trivial to fill the shoes of the mentally disabled and weak-kneed, but remarkably adaptable and inwardly tough, armed criminal Rey. Although Eric uses Rey to track down the criminals on the run who stole his car, by the end of the film it is not entirely clear who is using whom. All we know for sure is there are good guys and there are bad guys and bad guys are going to pay.

Well, the good guys are going to pay, too, because this is a film noir and nobody comes out completely unscathed, except for those who are spiritually dead to begin with.

The cinematography by emerging lenser Natasha Braier follows past templates closely and, presumably, was heavily guided by the director. The film features a lot of long, slow takes that threaten to get too slow in the beginning of the film but pick up pace nicely in the last half. There is not a single car chase, a single knock-down drag-out fight and hardly a single gun-fight. The harsh backdrop of the barren desert broken up by only the occasional short train, the shack with failing clapboard blowing in the wind, the deserted carnival containers and the road that never ends tell the story.

This is no-man’s land and yet men are forced to live here. When Eric demands that the old woman tell him where the men went with his car, she replies they came in one way and went out the other, as all cars do. As it turns out, men come in and go out in much the same way. Nothing changes in the desert and nothing changes in the outside world, either. Nobody comes to get murderers who will probably only bribe their way out of justice. Still, there is a point, if only the high plains drifter knows what it is.