Change the things you can, accept the things you cannot, and go to jail and die either way.

Nominated for the 2015 Academy Awards Best Foreign Film Oscar, and the winner of the Golden Globe, writer/director Andrey Zvyagintsev’s neo-biblical tome is as fascinating to watch as it is dreadful to imagine. Co-written with Oleg Negin, the screenplay is set in a small, nearly abandoned coastal town on the Barents Sea in northern Russia. All hope seems to have left the family of Kolya (Alexei Serebriakov). A small but successful automobile mechanic, the widower Kolya is embroiled in a fight with the corrupt mayor of his town over the forced sale of his property and repair shop.

Nominated for the 2015 Academy Awards Best Foreign Film Oscar, and the winner of the Golden Globe, writer/director Andrey Zvyagintsev’s neo-biblical tome is as fascinating to watch as it is dreadful to imagine. Co-written with Oleg Negin, the screenplay is set in a small, nearly abandoned coastal town on the Barents Sea in northern Russia. All hope seems to have left the family of Kolya (Alexei Serebriakov). A small but successful automobile mechanic, the widower Kolya is embroiled in a fight with the corrupt mayor of his town over the forced sale of his property and repair shop.

Think David and Goliath where David drinks too much.

Zvyagintsev was working in the United States when he heard the story of Coloradan Marvin Heemeyer, the creator of the so-called Killdozer. Heemeyer went on a suicidal rampage after a series of court actions denied him what he thought was a fair shake for his property and muffler repair shop. The biblical book of Job also provides context for the screenplay.

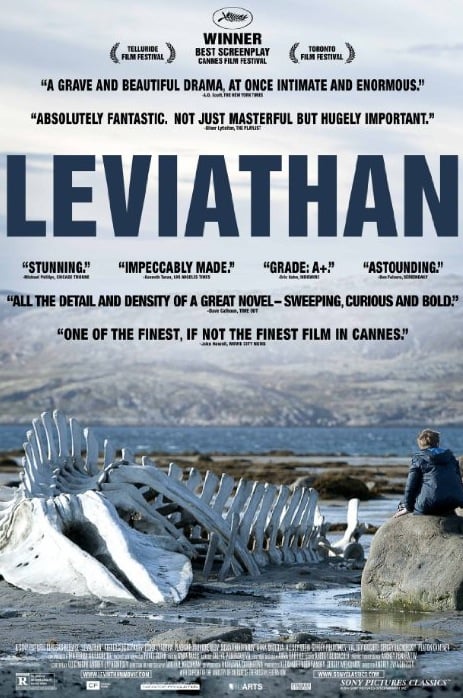

As the film unfolds we learn that the current chain of events is only the last in a bad decade for Kolya, his second wife Lilya (Elena Lyadova) and his son Roman (Sergey Pokhodaev). It is also the latest chapter in a bad century for their small town. Once a prosperous fishing village, it is now the resting place of whale skeletons and rotting boat carcasses.

In spite of that, things are changing. Capitalist Mayor Vadim Shelevyat (Roman Madyanov) sees a future for the town as a tourist center. Indeed, given the breathtaking scenery of the misty fiords of the Kirovsk Murmansk region this is not out of the question. The wind blows constantly and the sea crashes against the cliffs in a magnificent setting. Only one thing stands in his way, the stubbornness of the repair shop owner who is insisting on triple the amount of money the mayor is willing to pay.

Kolya’s faith in himself and his ideals is tested, as was that of Job. But this story is more complicated. Kolya is a flawed man. Although he has a right to strike a fair bargain, he has the temper tantrums of a child and drinks vodka at the rate of gallons per day. As it turns out, even the Russian authorities thought the film went too far in this regard and that the world would think of Russia as a country of simple, brutal drunkards.

In fact, it would have been a better movie without the excess of liquor, as we would have been better able to identify with the plight of Kolya. He hires his old friend Dmitriy, now a skilled attorney from Moscow (played by Vladimir Vdovichenkov) to represent him. But just when he seems to be gaining leverage, the bottom falls out. By the end of the film his own unbendable principles become his undoing and hubris appears to have taken the place of integrity.

Roman Madyanov’s Mayor Vadim, on the other hand, at first appearing to be just a greedy gangster, emerges as a man with at least a practical point of view about the future of the town and Kolya’s collapsing house and shop. You will have to be the judge Change what you can, accept what you cannot, or be prepared to deal with the consequences.

Nominated for the top prize at 2014 Cannes, the Palme d’Or, the film won Best Screenplay for Zvyagintsev and Negin. The sound track by Philip Glass, parts of his Akhnaten Act 1, is a perfect accompaniment to the grandeur of the constantly thrashing and crashing sea, the constant wind, the rain and the skeletal remains of the fishing boats and whales alike. Nobody comes out of this movie unscathed. Even worse, there is no anchor left with which to tie our floundering morals.

Perhaps the film was also influenced by the 2009 event in the Murmansk region where the film was shot. A local businessman, angry over local taxes and fees, shot the mayor and his deputy for housing, and then killed himself.